By: Frank Nieves, M.A.

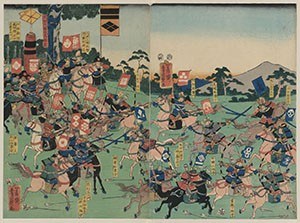

Over the centuries the philosophy of Japanese martial arts has gone through numerous transformations in order to conform to the demands of its ever-changing Japanese society. Prior to the Edo period (1603-1868), which marked an era of nationwide peace in Japan, the philosophy of budo, then known as bujutsu, was in its most primitive of stages. This period is known as the Sengoku Jidai (Warring States Period- 1467-1603), an era which saw a nation in civil war and political unrest. The philosophy of bujutsu, as its suffix -jutsu suggests, is simple; to train in the martial arts for the purpose of defeating the enemy. Martial arts from this period saw little in its efforts to establish a strict moral and ethical system to live by and focused more effectively on the tasks at hand; to develop able-bodied skilled soldiers that were loyal to their warlords.

As the Tokugawa Shogunate came to power in 1603, it brought with it a system of governing that would maintain peace throughout Japan for the next 250 years. This change in political policy would leave a lasting impression on martial arts philosophy. Without war, the need to train for the purpose of defeating an enemy was eliminated. This realization would transform bujutsu to budo. The change in suffix from –jutsu to –do suggests a significant shift in ideology, placing the emphasis on training to develop a better individual through arduous practice which in turn instilled the exponent with a strict moral and ethical code known as bushido (the way of the warrior), a code popularized in the 18th century by Yamamoto Tsunetomo through his book, Hagakure. During this period the martial arts flourished, leading to the creation of hundreds of new schools. Although these schools varied in their technical application of the martial arts, they were all deeply rooted in the bushido ethos. They all focused on the development of skilled and morally grounded practitioners. This shift in philosophy would remain in place to this day and lay the groundwork for the modernization of the martial arts in the times to come.

In 1868, the Meiji restoration would bring an end to the Tokugawa Shogunate and mark the beginning of Japan’s modernization and westernization period. This new beginning would have a tremendous impact on the martial arts of Japan. As Japan struggled to catch-up with the Western world after 250 years of isolation, they attempted to strip away any remnants of their feudal samurai past. In 1869, they abolished the samurai class and by 1876 they were deprived of wearing daisho (matched pair of samurai swords). With the samurai class eliminated and Japan heading into a Westernized system of governing, the future of Japanese martial arts seemed futile.

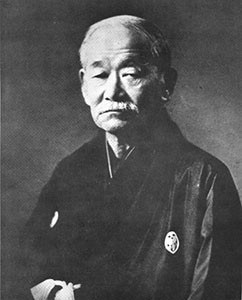

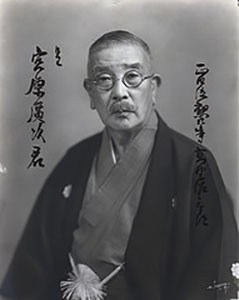

By 1872, the Ministry of Education was beginning to take form and was searching for a way of conserving Japanese culture while simultaneously instilling the youth of Japan with a correct moral code negligent of religious ideals. The Ministry of Education would turn to the Dai Nippon Butokukai (Greater Japan Martial Virtues Society), established in 1895 and charged with the task of preserving budo, to devise a standard system of martial arts training that would not only be safe for the youth of Japan but provide them with a proper system of moral education. The result was the standardization of judo, through its founder Kano Jigoro, and Kendo, through the efforts of Takano Sasaburo. These men would lay the foundation for what would become modern judo and kendo today, suitable for all men, women, and children regardless of age, social class, or creed. The martial arts philosophy put forth by these pioneers would become the staple for all modern martial arts to follow.

Kano Jigoro’s budo philosophy was summarized best when he stated, “Budo is the way of the highest or most efficient use of both physical and mental energy. Through training in the techniques in budo, the practitioners nurture their physical and mental strength, and gradually embody the essence of the ‘Way’. Thus, the ultimate objective of budo is self-perfection, and to make a positive contribution to society.” As the recipient of these words, one can fully understand that modern budo goes beyond defeating foe and delves into conquering the self which in turn will improve the lives of those who come in contact with us. Therefore, in order to fulfill the commitment to proper martial arts training as set forth by the great masters of the modern martial arts we must not only focus on the technical aspects of the arts but endeavor to become better individuals through its practice. In order to do so we must understand the guidelines put into place to help us achieve this ultimate goal.

The guidelines for proper practice of modern budo encompass several key elements. Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that modern budo is both a martial art and a competitive sport, and therefore requires dedicated attention to fitness, exercise, nutrition, and hygiene. These factors are essential in creating an optimal training environment. Secondly, discipline is crucial to maintaining focus and achieving progress. Practitioners must demonstrate self-respect, respect for training partners, punctuality, loyalty to the dojo, and cleanliness of oneself, equipment, and training facility. Thirdly, order must be maintained through adherence to the traditional hierarchy of martial arts, which derives from its military origins. Lastly, education is a vital component of a budoka’s development. This involves a commitment to broadening one’s understanding of the martial arts through literature and seminars, in addition to practical training. It is essential for a martial arts practitioner to continually seek knowledge and enrich their understanding of the arts, following in the footsteps of the great masters.